Féroce meets: Kári Þór Barry

We previously featured the Frivolous Cartoons collection for its sharp use of humour, exaggeration and tailoring as critique. In this interview, the designer expands on the ideas behind the work, from cartoon gangster archetypes and performative masculinity to the decline of bespoke menswear and the role of play in contemporary fashion. What emerges is a thoughtful reflection on taste, access and the artificial codes we continue to dress by.

1. What first drew you to the visual world of old cartoon gangsters, and why did you feel

it was a fitting foundation for a contemporary menswear collection?

I chose cartoons because of a photo from Tom and Jerry. The picture shows Tom wearing a very snazzy suit. After examining the suit he wore more closely, I found that it was a historical reference to the American zoot suit, which was widely popular among minorities in urban areas of the US during the 1920s. The suit consists of a long, drapey frock coat and very wide-legged trousers. This particular picture then led me down a rabbit hole into the world of cartoon suits and how banal they can look, such as in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit. The film blurs the line between the real world and cartoons, as seen in the crew of mischievous weasels, Toon Patrol, who serve as the film’s main antagonists. In this band of weasels, the Italian-American gangster trope is very obviously at work in the crew’s dress: they all wear form-fitting suits and are armed with Tommy guns.

2. The collection title Frivolous Cartoons suggests both humour and critique. What does the word frivolous mean to you in this context?

I chose the word “frivolous” because I associate it with the Toon Patrol, whom I reference a lot in my collection. The literal meaning of being frivolous is to be goofy or just plain useless.

“I really wanted the people who wore my collection to look like they meant business, but in reality, they are useless, just like the Toon Patrol.”

3. How did you translate exaggerated, animated character traits into real garments without losing their sense of play? What can you tell us about your process?

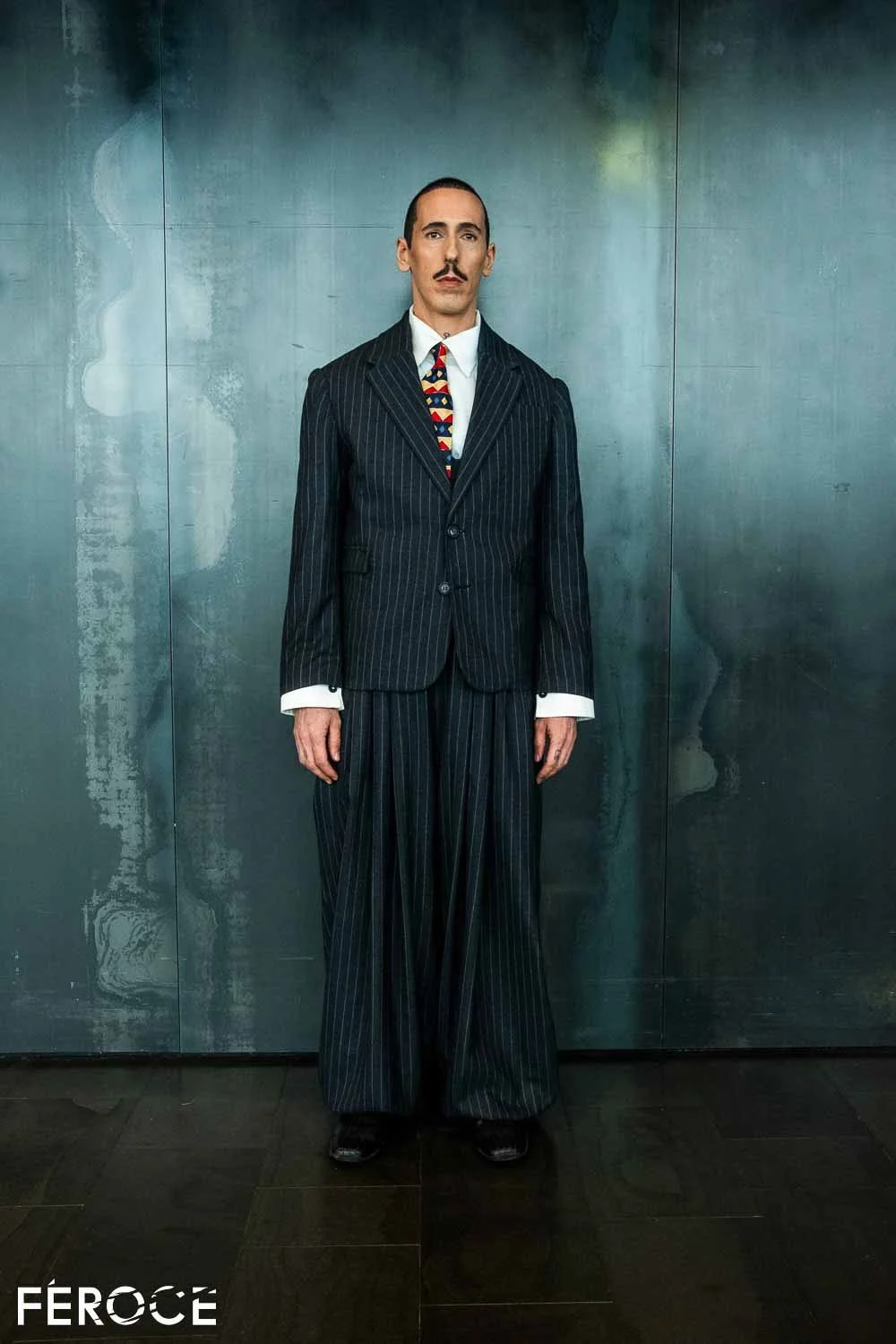

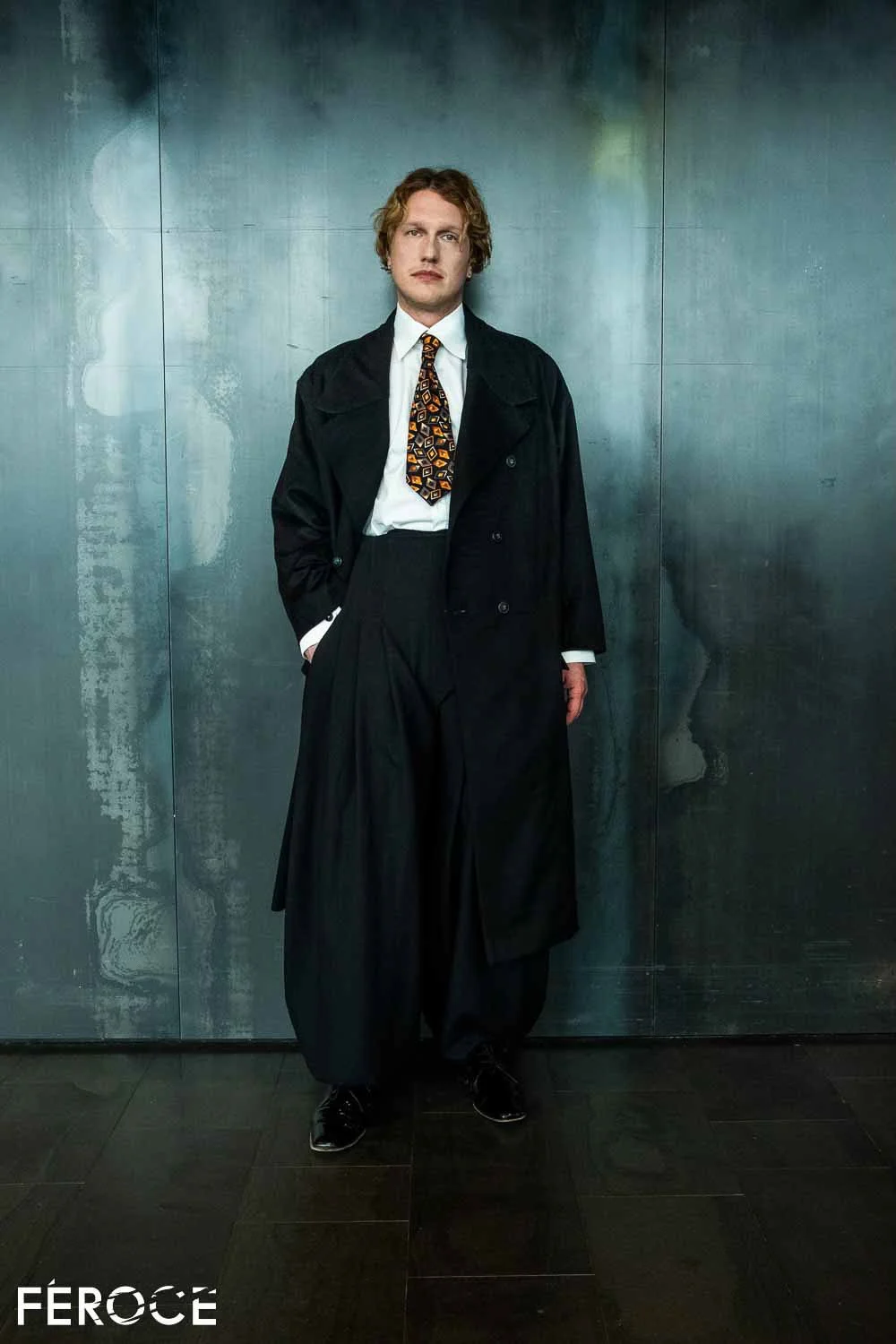

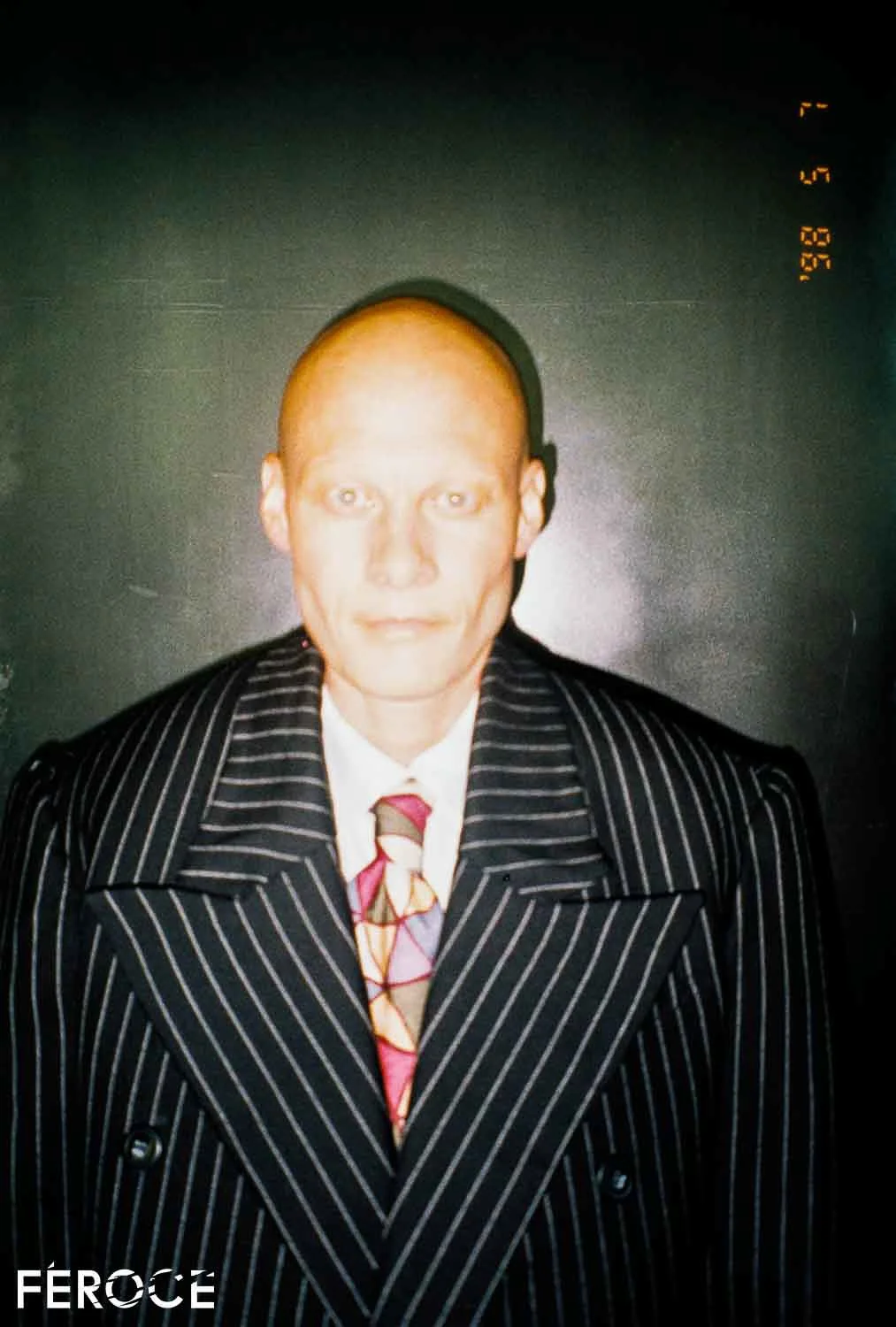

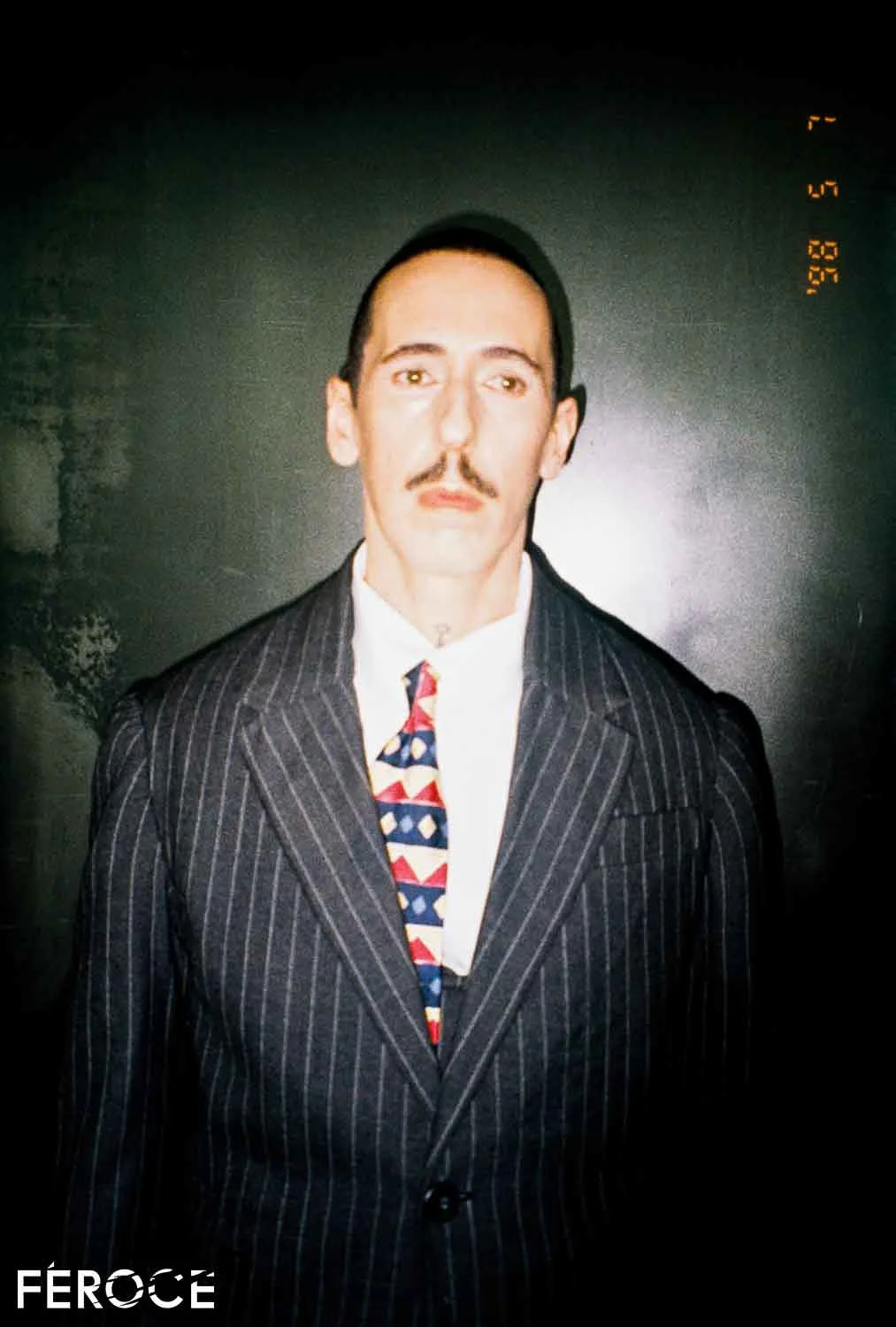

By both identifying and researching the exaggerations of suits in cartoons, I could translate them into reality by using tailoring to my advantage. Then there was the task of finding the right face for the outfit, someone who could really live into the role.

4. Each look feels like a specific persona stepped out of a frame. Did you develop individual characters while designing?

The casting was crucial in my process; while designing each outfit, I associated a specific character with it, and finding the right face for the outfit was essential. I had to find models who could play the part, so I gravitated towards actors; most of my models were working actors, and they understood their character and lived it.

5. How do you see humour functioning within menswear, and what do you think playful design can say that traditional tailoring does not?

“Traditional tailoring, in its current form, serves only the elite. It’s a time-consuming art that only the wealthy can afford. At the same time, the wealthy are immensely boring, so no wonder you don’t often see fun suits any more, just well-made suits.”

The few places you can actually see interesting suits, apart from the odd outfit during fashion weeks, are when students make them. Playful design and traditional tailoring should and can work together. We use tailoring to achieve something fun, but that can only happen when more people can afford a bespoke suit, not just a select few.

6. Cartoon gangster imagery is rooted in an era of caricature, hyper-masculinity, and slapstick violence. Did you engage with these themes critically in your work?

I engaged with them critically, and my thesis statement was to explore the aesthetics of cartoons and how they could be effectively translated into fashion. To do this, I researched the origins and symbolism of caricature and how it has been used in popular media throughout its history, which can be traced back to ancient human cave paintings. My work draws heavily on the visual language of cartoon gangster imagery, and I am aware that it is historically tied to exaggerated masculinity, racialised caricature, and slapstick violence.

“I wanted to highlight how artificial and performative these tropes are, so I deliberately employed these elements by exaggerating certain traits, identifying historical references, and casting the right model.”

7. Do you see the collection as a commentary on fashion, masculinity, or nostalgia?

My work is a commentary on the decline of bespoke tailoring in fashion. As wealth concentrates at the top and fast fashion dominates, the tailored suit has become incredibly inaccessible and has almost been completely overtaken by off-the-rack suits, the production of which focuses almost entirely on cost reduction and mass production.

“My project reimagines tailoring as something playful and expressive, rather than exclusive.”

8. What does translating animation into real life say about the boundaries between fantasy and clothing?

What I realised during this project is that there is a very thin line that should be crossed more often in fashion, especially in tailoring. Animation allows for exaggeration, distortion, and the absurd, and, by transferring these qualities into fashion/tailoring, enables clothing to communicate identity, narrative, and emotion more expressively and unconventionally, rather than focusing solely on utility.

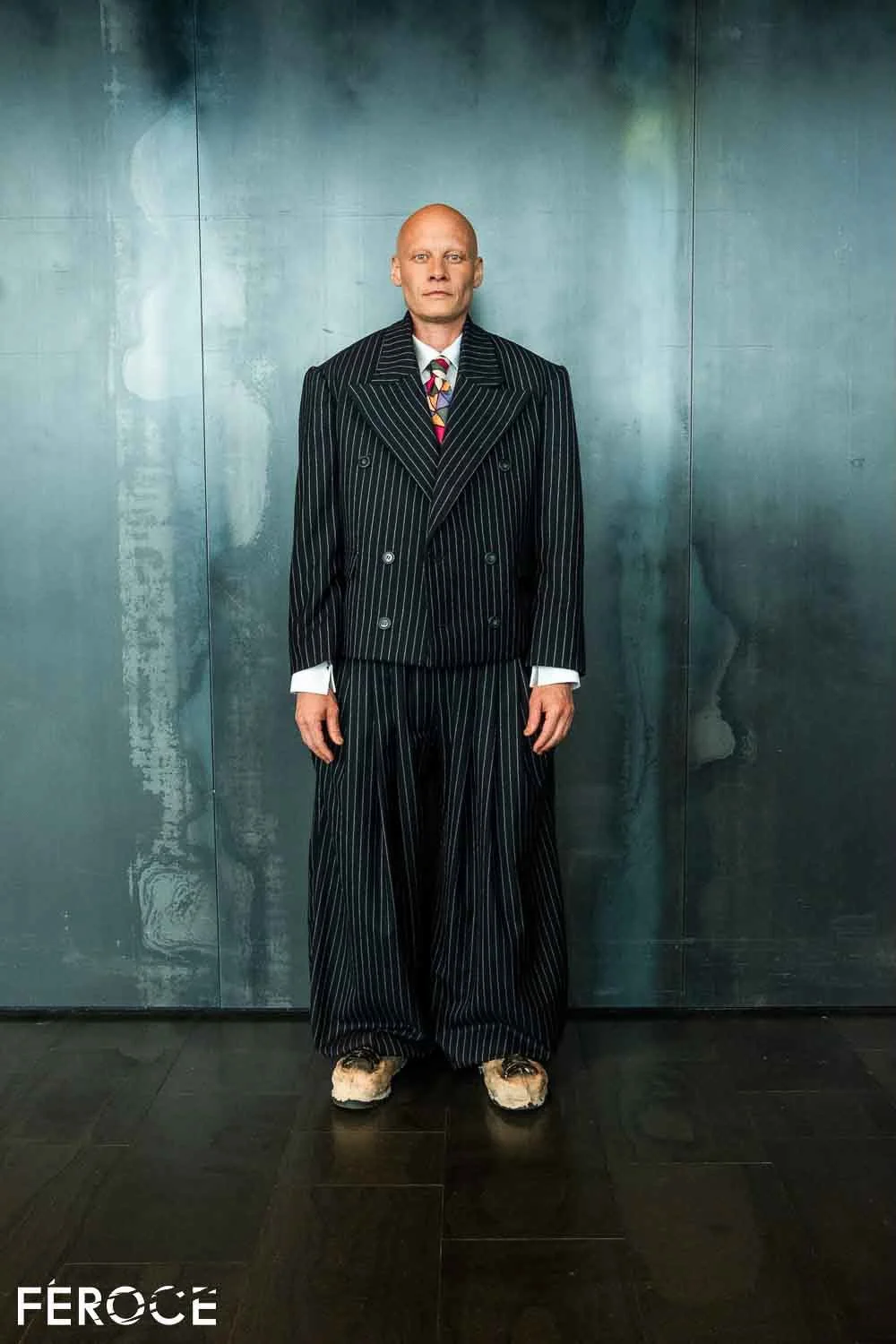

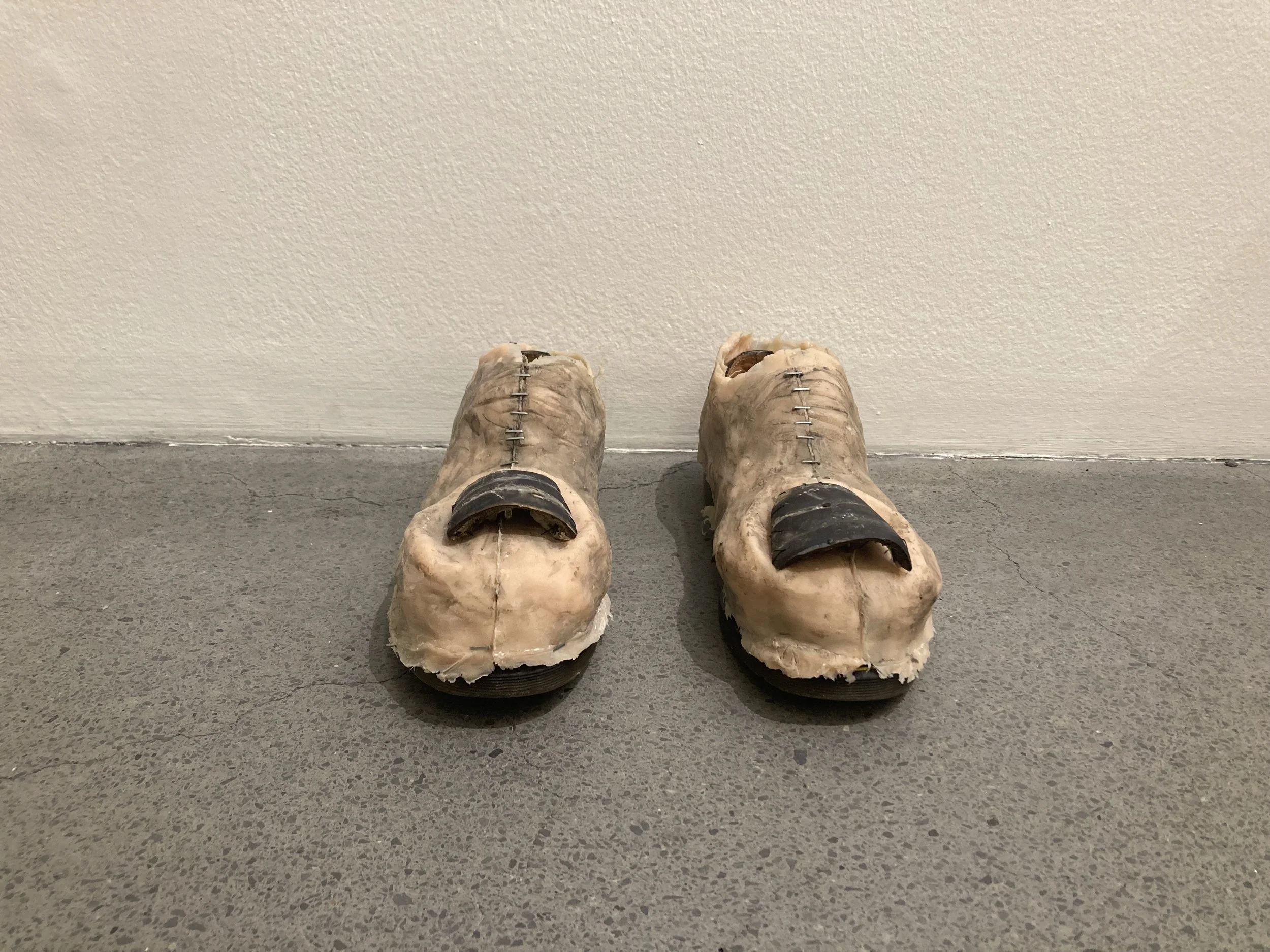

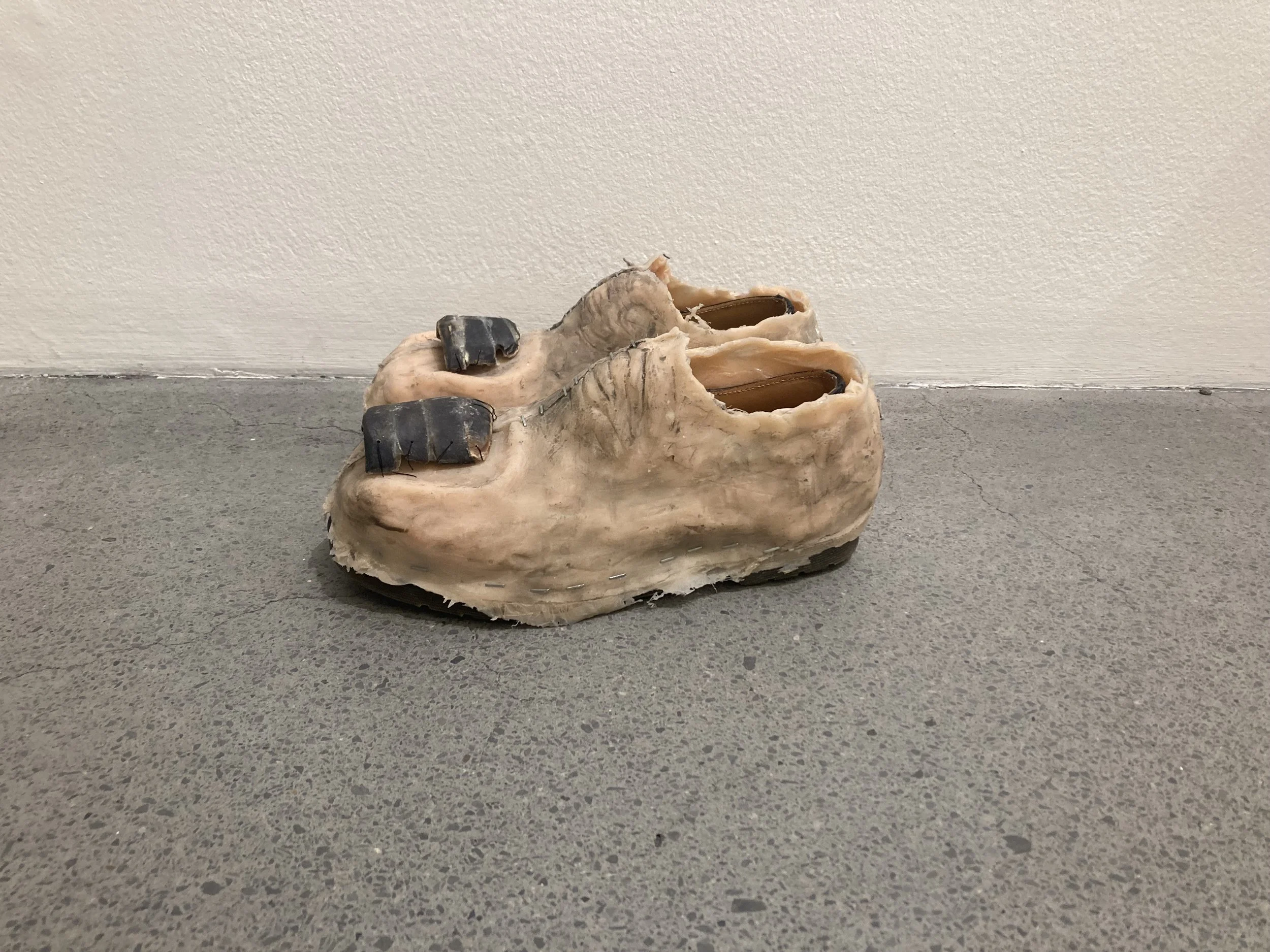

9. Please tell us all about the toe boot. WHAT were you thinking? To us, it looks like a

representation of what would be on the inside of a cartoon boot if proportions matched

clothes. Please do let us know!

The Toe Boot came to me when I poorly sketched a pair of stilettos and realised that they resembled a toe or a finger. The concept developed further when I rewatched the film Spy Kids, another film that blurs the line between reality and cartoons. What struck me in the film were the characters Thumb Thumbs, humanoid figures that resemble five thumbs squashed together, and it instantly reminded me of the toe boots I had conceptualised. I wanted the boots to be a stark contrast to the suit and as real and gross as possible. I moulded the shoe in my vision from clay, took a plaster cast of it, then poured skin-coloured silicone into the cast, and that’s how the base shoe was made. Then I had to make the toenail and realised that the material in our fingernails and horse hooves is the same.

“After many odd emails to different stables, I finally managed to source a bag of horse hoof clippings, which I then cut and moulded into my desired shape, and finally brushed on some nice lacquer to get a nice glossy finish.”

-

http://www.instagram.com/karithorbarry_

School Ig: http://www.instagram.com/iua_fashion_design

link to Designblok website: https://www.designblok.cz/cz/diploma-selection#finaliste